St. John Marie Vianney - The Man Who Could See Souls

Feast Day: August 4 | Patron of Parish Priests | Confessor to the World

Halo & Light Studios

8/5/20254 min read

Click Link for a reel of Daily Dose of Saints and Faithful Art:

https://youtube.com/shorts/NOMflYrQGxc

The fog lay heavy over the fields of Ars that morning—damp, gray, reluctant to lift. It clung to the cobbled road like sin to a weary conscience. Somewhere in the distance, a bell tolled, muffled and far off, as if even heaven itself held its breath.

And then, from beneath the haze, a figure emerged.

A thin man in a black cassock, walking slowly toward the church. His gait was tired but steady. His face, pale and worn by penance, bore the lines of long vigils, fierce temptations, and the weight of many souls. His eyes—intense, kind, deeply knowing—looked as if they had peered straight into eternity.

This was Jean-Marie Baptiste Vianney, the Curé of Ars.

To understand this priest, you must first understand his battlefield.

France in the early 1800s was a nation still bleeding from the French Revolution (1789–1799). The Church had been its primary target: convents looted, bishops guillotined, statues beheaded, and priests hunted like criminals. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy (1790) had forced clergy to swear allegiance to the revolutionary state over the pope. Thousands refused, going underground or to the scaffold.

By the time of Vianney’s youth, the damage was incalculable. Entire generations had grown up without catechesis, confession, or Mass. The priesthood was seen as obsolete, even shameful. France, the “eldest daughter of the Church,” had become one of her greatest wounds.

The few priests who remained were often demoralized or poorly formed. Eucharistic devotion was rare. Confession had become a relic. Vocations were nearly extinct. The devil had scattered the flock. But God would raise up a shepherd.

Born May 8, 1786, in Dardilly near Lyon, John Vianney grew up with the image of hidden Masses and fugitive priests. As a child, he watched his family host secret catechesis, and he received his First Communion in a barn. Priests arrived in disguise. The Eucharist was smuggled like contraband. These moments lit something deep within him: a longing for the altar, and a love for souls who had forgotten God.

Though deeply devout, John was a poor student—especially in Latin. He failed seminary entrance exams multiple times and was dismissed twice. But his perseverance was saintly. His mentor, Abbé Balley, fought to keep his vocation alive. Finally, in 1815, at age 29, he was ordained. Not for brilliance—but for holiness.

Three years later, in 1818, Fr. Vianney was sent to Ars, a tiny farming village in southeastern France. It was spiritually dead: Sunday Mass was ignored, sacramental life non-existent, and the local tavern did more business than the church.

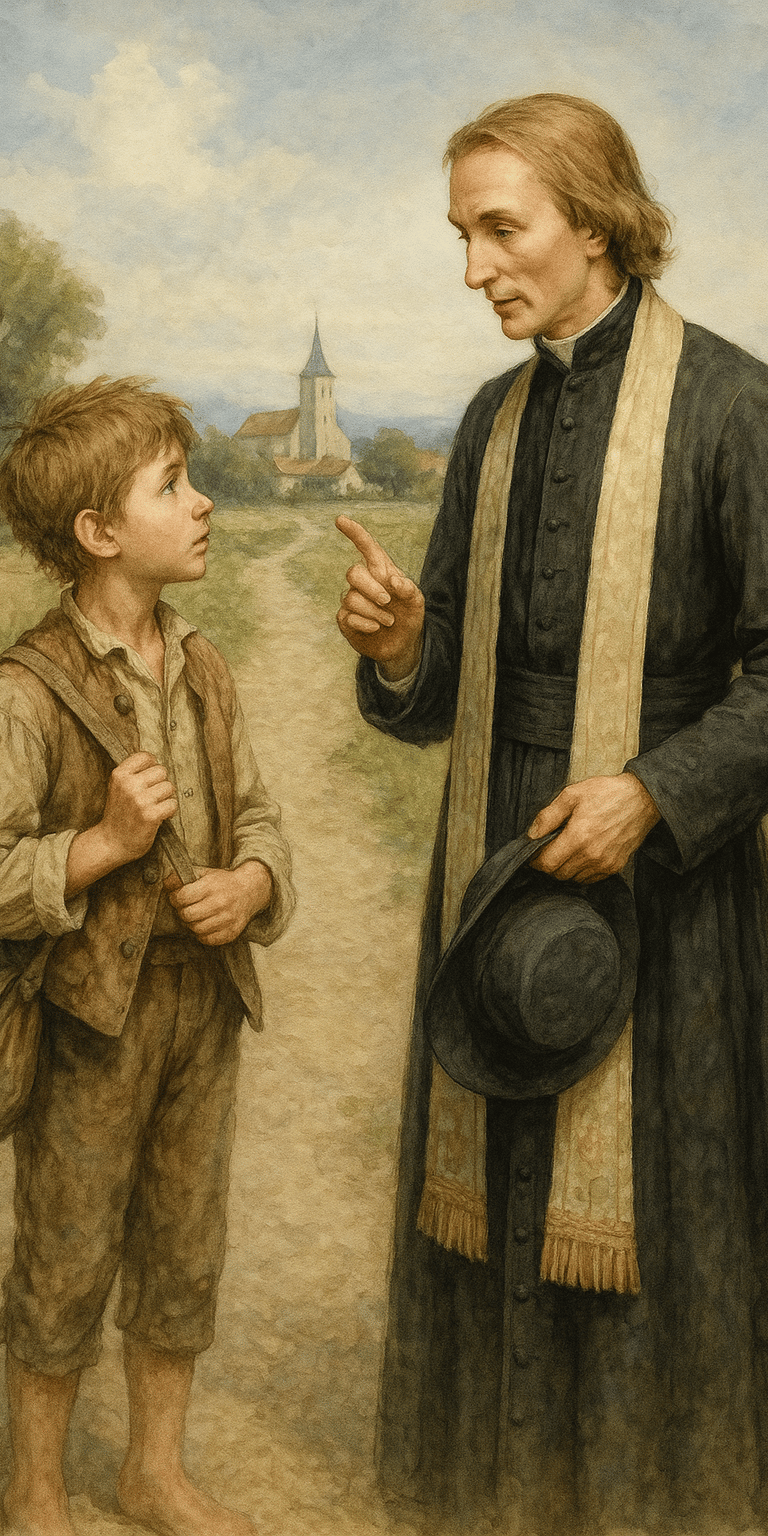

When he asked directions to the village, a boy famously told him, “You are going the wrong way.”

Vianney replied, “Then show me the way to Ars, and I will show you the way to Heaven.”

Fr. Vianney began his mission with tears and fasting. He rarely ate more than a boiled potato and spent hours in Eucharistic adoration, pleading for the conversion of his parish. He practiced extreme penance—sleeping only a few hours on a straw mattress, wearing a hair shirt, and scourging himself for reparation.

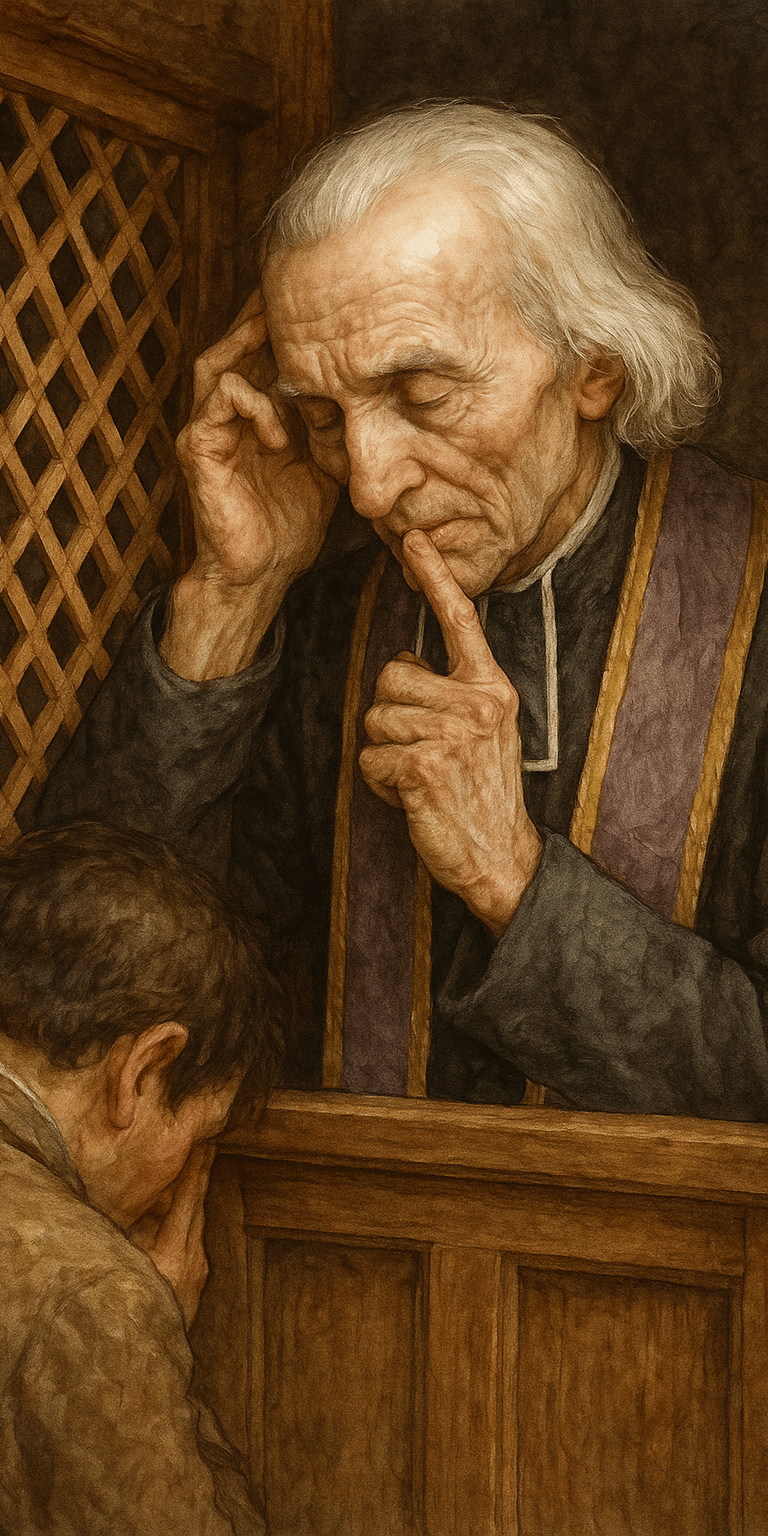

And slowly, fruit began to blossom. Confessions returned. Families came back to Mass. Taverns emptied. Children learned their catechism. By the 1830s, people from across France were making pilgrimages to Ars. By the 1850s, up to 20,000 visitors a year—peasants and nobles alike—waited days just to enter his confessional.

He read souls. He performed miracles. He cast out demons. He whispered to sinners what they had never told anyone. And most of all, he never ceased to say: “God is more eager to forgive us than a mother is to snatch her child from the fire.”

He gave away every gift he received—money, food, even his own bed. When honored with the French Legion of Honor, he sold the medal and gave the money to the poor. He founded La Providence, a home for orphaned girls, trusting entirely in Divine Providence for its survival. His spiritual power lay in the Eucharist. “If we understood the value of the Holy Mass,” he said, “we would die of joy.”

For 35 years, Fr. Vianney endured nightly attacks from the devil—furniture thrown, footsteps in the dark, shrieks and fires. Once, his bed was engulfed in flames. He named his tormentor “le grappin”—“the pitchfork.” And he knew why. “The devil is angry,” he said, “because I bring so many souls to God.”

In his last years, he attempted several times to leave Ars in secret—feeling unworthy. But his parishioners always found him and brought him home. In 1859, worn out by decades of fasting, confessions, and self-gift, he died on August 4 at age 73. His body was found to be incorrupt and remains venerated in Ars to this day.

He was canonized in 1925 and declared Patron of Parish Priests in 1929 by Pope Pius XI.

St. John Vianney lived at a time when the Church was mocked, the priesthood scorned, and the sacraments neglected. Sound familiar? He responded—not with complaints, but with the Cross. Not with strategy, but with sanctity. And not with worldly cleverness, but with a burning love for Christ in the Eucharist and a fierce tenderness for lost souls.

His message is timeless: “There is no such thing as a bad priest, only one who is not yet a saint.”

When we despair of the world’s darkness, we must remember: one priest, holy and hidden, can set a nation on fire.

Let us pray for our priests. Let us return to Confession. Let us fall in love again with the Eucharist.

St. John Vianney, Confessor of Souls, pray for us and the conversion of your beloved France.